Climate Ambition: COP 26 and Beyond

Aditi Sinha, March 6, 2022

In about a week from today, world leaders will gather at COP26 in Glasgow. The pressure is on for countries to urgently ramp up their ambitions for global collective action on climate change. The latest IPCC report speaks volumes about the challenge ahead—the world has only a very narrow pathway to limit warming to 1.5 degrees C, the limit scientists say is necessary for averting the worst of climate disasters.

It is worthwhile to remember that COP 26 is taking place in a context that has never been seen before. Countries all over the world are recovering from the ravages of COVID-19. The impact of climate change is becoming more visible from extreme weather events to the loss of people’s livelihoods. In the run up to COP 26, several nations announced net zero targets putting the spotlight on India to do the same.

The goal at COP26 is to get countries to enhance their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) agreed to under the Paris Agreement. But progress at COP 26 depends to a large extent on how well the issue of climate finance and equity will be addressed in the negotiations.

Can Climate Finance Be The Remedy To The Trust Deficit Looming Over COP 26?

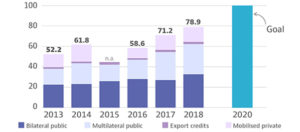

The climate finance gap is being viewed as a major stumbling block for COP26. More than a decade ago, developed countries pledged to mobilize $100 billion annually by 2020 to enhance climate action by developing countries. But the OECD recently estimated developed countries mobilized $79.6 billion in climate finance in 2019, falling short of this vital commitment (see figure below).The report also shows that the finance flows stagnated even before the global pandemic.

Image credit : Climate Finance Provided and Mobilised by Developed Countries (OECD 2021)

Recent research from the World Resources Institute (WRI) finds that three major economies — the United States, Australia, and Canada — provided less than half their share of the financial effort committed way back in 2018.

The UN NDC synthesis report emphasizes that NDCs submitted by several developing countries included conditional commitments to cut down on emissions. But these could only be fulfilled with access to additional finances and other support, particularly for adaptation measures.

Echoing this sentiment, India called upon developed countries to fulfil their promise of climate financing, asserting that “COP26 should focus on climate finance in scope, scale and speed and transfer of green technologies at low cost.“ On a positive note, US President Biden’s recent pledge to double climate finance for developing countries comes as a welcome move, but it still falls short of what is actually the need of the hour.

Sizing Up The NDCs Globally

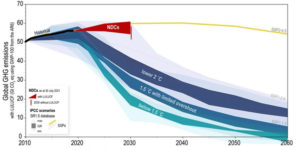

The NDCs lie at the heart of the Paris Agreement. The recently released UN NDC synthesis report sized up NDCs from around the globe. It acknowledges the trend of greenhouse gas emissions being reduced over time, but also warns that countries must urgently redouble their climate efforts if they are to prevent global temperature increases beyond the Paris Agreement’s goal of well below 2C – ideally 1.5C – by the end of the century.

The report reveals some alarming findings—the available climate plans of all 191 parties together implies a sizeable increase of about 16% in global GHG emissions in 2030 as compared to 2010.

It is amply clear that each party must stand committed to intensify its efforts lest we stare at a disaster in the making for all mankind.

Net Zero Is A Pipe Dream Without Total Inclusion

From running one of the largest and most ambitious renewable capacity expansion programs in the world, to spearheading global climate partnerships, India has taken massive strides.

While these actions are well-recognized, the key question is whether India is in a position to announce a long-term target such as net zero emissions by 2050. Ahead of COP 26, several countries announced net zero pledges, including the USA and China by 2050 and 2060 respectively.

But for a country like India, choosing a net-zero year is not a simple task. India’s national circumstances and the feasibility of achieving net-zero, particularly in the context of the development needs of the vast majority of its population, should be carefully considered before such a long-term commitment can be made.

In a joint op-ed, Dr Anshu Bhardwaj, Shakti CEO and Shri Jayant Sinha, Chairman of the standing Committee on Finance in Parliament, point out that “there are many potential paths to a green future, including net zero, all of which require a detailed analysis to determine the best course for India.” They underscore that India is already on a low-carbon growth trajectory by demonstrating that economic growth does not have to go together with the consumption of fossil fuels and increasing emissions.

India’s energy transition has wider implications. Mr. Jamshyd Godrej, Shakti Board Chair and Industry leader and Fatih Birol Executive Director of the IEA, opine in a joint op-ed that India’s energy transition must be just, people centric and focus on gender equity and social inclusion. They add that in “India’s case, new jobs would need to be found over time for the coal miners affected by the changes, as well as for people who work in the fossil fuel power plants that will be closed down.” Clearly, the need for equity is significant not just in terms of India’s response to net-zero globally but also for India’s own growth trajectory.

India is Seeking a Level Playing Field

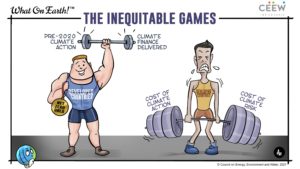

But inequitable climate goals are unfairly burdening developing countries. The 2050 net zero goal should be based on the principles of equity, and common but differentiated responsibilities. Anything else is unjust and undesirable. India’s energy transition has wider implications. Mr. Jamshyd Godrej, Shakti Board Chair and Industry leader and Fatih Birol Executive Director of the IEA, opine in a joint op-ed that India’s energy transition must be just, people centric and focus on gender equity and social inclusion. They add that in “India’s case, new jobs would need to be found over time for the coal miners affected by the changes, as well as for people who work in the fossil fuel power plants that will be closed down.” Clearly, the need for equity is significant not just in terms of India’s response to net-zero globally but also for India’s own growth trajectory.

India is seeking a level playing field. But inequitable climate goals are unfairly burdening developing countries. The 2050 net zero goal should be based on the principles of equity, and common but differentiated responsibilities. Anything else is unjust and undesirable.

Image credit : What On Earth, CEEW (2021)

Aditi Sinha is Associate Director – Communications at Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation.